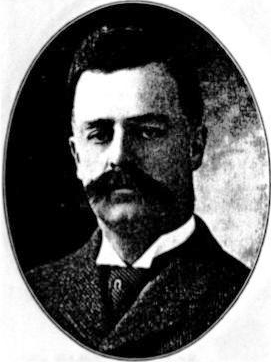

Albert Cameron Burrage was born in Ashburnham, Massachusetts on November 21, 1859. His parents were George S. and Aurelia Chamberlin Burrage, descendants of old New England families. John Burrage arrived from England in 1636. When Albert Burrage was three, the family moved West.

Throughout his life, Burrage had an allegiance both to Massachusetts and the Western states. Educated in California, he graduated from Harvard University in 1883 with an A.B. degree. He married Alice Hathaway Haskell in 1885. The couple had four children: Albert Cameron, Jr., Francis H., Elizabeth A. (Mrs. Harold L. Chalifoux), and Russell.

In 1884 Burrage was admitted to the Massachusetts bar and began his career as a lawyer. He was named counsel for the Brookline Gas Light Company in 1892. Later he became president of the Boston, South Boston, Roxbury, and Dorchester Gas Light companies and the Bay State Gas Company. In 1898, he

resigned these positions because cities were starting to switch to electricity for lighting and his interest had turned to copper mining on a large scale. He organized the Amalgamated Copper Company and was one of the founders of the Chile Exploration Company and of the Chile Copper Company. He pursued the development of new processes for the treatment of low-grade copper ores. By the end of the century, Burrage had major roles in both Amalgamated Copper and Standard Oil and was regarded as one of the preeminent men of the era. He remained a director of Amalgamated Copper until it was dissolved during the era of President Theodore Roosevelt’s trust-busters.

Burrage was active in Boston’s civic, political and social circles. He served on the Boston Common Council in 1892, getting approval of the “Burrage Ordinance” which prohibited city employees from being members of a political action group. He was a member of the Boston Transit Commission that built

the Boston subway system. In politics he was a Republican. He was affiliated with many clubs including the Harvard, Union, Algonquin, Boston Art, Country and Eastern Clubs. In New York, he joined the Bankers Club and New York Yacht Club.

A philanthropist, Burrage donated the funds to build the Burrage Hospital for Crippled Children in Boston. During World War I, he loaned his 260 foot, steam powered yacht and other personal assets, to the government to assist the war effort.

However, Burrage was upset about the condition of the Aztec when it was returned to him after the war. He filed a claim with the government for $325,000 in repairs and $60,000 for the loss of use of the yacht. His attorney, the Hon. William Gibbs McAdoo, succeeded in getting $300,000.

He traveled widely, but Boston was the location of his main office and residence. In 1899 he built an imposing mansion at 314 Commonwealth Avenue in the Back Bay section of the city. The architect was the notable Charles Brigham. The multi-story home was designed in the manner of the Vanderbilt House in New York, which itself was inspired by the French chateau Chenonceaux in the Loire Valley. For the construction, Burrage used the finest materials-European marble, rare mahogany, stained glass windows and intricately designed mosaic tiles. The exterior has nearly 50 dragons and gargoyles, 30 cherubs, 300 bibliophiles, and lion, eagle, and human heads carved into the elaborate stonework. The mansion was a reflection of Burrage’s success as an entrepreneur and of his personal wealth.

In 1901 Burrage built a huge 28 room estate at 1205 West Crescent Avenue in Redlands, California. It was also designed by architect Charles Brigham. Occupied for only two months a year for several years, the mansion was mainly used for entertaining. The Burrage polo ponies were transported there by

private Pullman car so guests could play polo on the grounds. There were elaborate parties in the glass-covered swimming pool, which could be covered by a wooden floor for dancing.

During World War I there was high demand for dyestuffs and many entrepreneurs risked capital to establish domestic manufacturing facilities. In 1916 Burrage started the Atlantic Dyestuff Company in Boston with capital of $0.5 million, later increased to $1.0 million. His brother Charles, also a lawyer, was treasurer and his son Albert Jr. was a director. The first plant was established near Hanson, Massachusetts but was destroyed by fire in 1919. A new plant was built in 1920 at Newington, New Hampshire. Sales offices were setup in New England, New York, Chicago, Charlotte and other locations where textiles were produced.

After a strong start in the early 1920’s, Atlantic Dyestuff faced fierce competition from larger dye producers who had the advantage of lower raw material and production costs. The company went bankrupt in 1925 and was reorganized as the Portsmouth Dye and Chemical Company. There was an attempt to diversify with rubber chemicals manufacturing, but the business failed by the time of the Great Depression in 1930.

The Atlantic Dyestuff Company was one of several chemical businesses that Burrage owned under a parent company called the Drugs and Dyestuffs Corporation of New York. Another division was the Charleston Chemical Company, located on a 40 acre site on the Kanawha River in Belle, West Virginia. This plant was engaged in the production of war chemicals during World War I until destroyed by fire in 1918. Production was resumed in a temporary building and plans were announced in 1920 to rebuild the plant and triple the capacity for organic chemicals. But the company fell on hard times and in 1922 Burrage won a judgement of $617, 575 for money that had been advanced and due on notes. The plant was auctioned in December 1922 and the property was acquired in 1925 by Du Pont for a synthetic ammonia plant.

Burrage was an avid horticulturalist and was well known for his tropical orchids. He was president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and the first president of the American Orchid Society in 1921. He authored the book “Burrage on Vegetables” and received the Lindley Medal of the Royal

Horticultural Society.

In 1921 Burrage purchased an estate in Manchester-by-the-Sea, a seaside community on Boston’s North Shore. The Georgian mansion was designed by the Little & Brown architectural firm and built in 1880. The Burrage family called it “Seahome” and used it primarily as a summer retreat. The eight-acre property, located on a private penisula with stunning views of the Atlantic Ocean, has a greenhouse, topiary garden, deepwater dock, oceanfront swimming pool, and a stretch of sandy beach.

In June 1931, Burrage attended the wedding of his granddaughter, Katherine Lee Burrage to Forrester A. Clark. The evening before, the Burrages hosted a dance aboard their yacht “Aztec” for the wedding party. On June 28, 1931, Burrage died at his summer estate Seahome. He had been in poor health for a

year. Survivors included his wife Alice and children Albert Jr., Russell, and Elizabeth (Mrs. Harold L. Chalifoux).

In 1911 Burrage had purchased at auction the gold collection of George de la Bouglise, a famous French mining engineer. This impressive collection of gold specimens, along with Bisbee azurites and malachites, was bequeathed to the Harvard Mineralogical Museum. His extensive library of horticultural books was donated to the Massachusetts Horticultural Society.

The Burrage wealth quickly disappeared after his death in 1931. His estate was thought to be worth almost $6.0 million. Alice Burrage found that the estate was valued at just $3.25 million. The Guggenheim Brothers contested the estate, since Burrage was heavily in debt to them for the Chile venture. In reality the estate was $1.8 million in the red. Alice Burrage used $1.8 million of her own money to settle the case. The sons of Burrage were in debt to their mother for hundreds of thousands of dollars and were listed as liabilities in her probate record of 1947.

References:

1) “Fire Destroys Large Belle Chemical Plant”, Charleston Daily Mail, October 7, 1918

2) “Chemical Plant Will Be Tripled in Capacity”, Charleston Daily Mail, March 23, 1920

3) “Award to A. Burrage Judgement of $617, 575”, Charleston Daily Mail, October 19, 1922

4) “Sale of Valuable Real and Personal Property”, Charleston Daily Mail, November 24, 1922

5) “Navy”, Time, April 28, 1924

6) “Du Pont Interests to Enter Kanawha VAlley; Buy Plants at Belle”, Charleston Gazette, April 30, 1925

7) “A.C. Burrage Dead; Boston Attorney”, The New York Times, June 30, 1931

8) Who Was Who in America, Vol. I, 1897-1942, Marquis Who’s Who Inc., Chicago, pp. 171-172

9) Marty D. Wolford, “Gargoyles!”, Boston Globe, March 4, 2004

10) “Hidden History”, Panorama Magazine: The Official Guide to Boston, www.panoramamagazine.com

11) Carl A. Francis, “An American Perspective on Russian Gold Specimens”, Rocks and Minerals, May-June 2004

12) “The Burrage House-Study Report”, Boston Landmarks Commission, Environment Department, City of Boston, ca. 2000

13) Merit McIntyre, personal communication, August 15-16, 2006

[ColorantsHistory.Org cites Merit McIntyre for his contributions to this biography.]